General to specific:

Expository writing and the artist

First things first

When writing (and talking), we usually provide

the most important general information first, and we add details later. That's also the foundation of

traditional journalistic writing. We begin with a headline, progress to a

lead sentence, and then follow with details.

When we talk, we say, "I saw a bank robbery this morning," and then we add details.

In technical reports, we begin with an executive summary and then add the details. But the critical information is always at the beginning. This is a general to specific format—general information first, followed by specific information. And that's the way Tom Lynch paints.

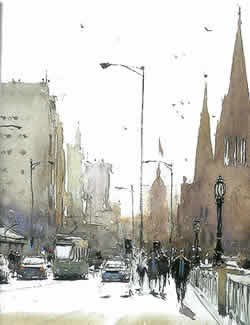

Lynch sometimes masks or covers parts of the paper and then puts in large masses of color, sometimes with a brush and sometimes with a spray bottle.

He then develops these masses into identifiable shapes by adding foreground and background detail until a painting suddenly appears. Tom Lynch thinks first about the big picture and then develops it into a more detailed work. The following painting is by Tom Lynch.

Beginning with detail

Other artists begin with detail (specifics) and

work toward a unified, more general painting. Watching Charles Reid draw a

detailed still life is quite an experience.

Reid adds color by not just staying inside the lines.

His paintings are good not only because of what he paints, but for what he leaves out.

Joseph Zbukvic begins with a highly detailed drawing and then fills in the spaces with color—generally staying inside the lines.

Adjoining colors often lack the contrast—light next to dark—that we've been told is so important. Nonetheless, his work is beautiful.

John Yardley uses the same technique—a detailed drawing followed by lots of neutral colors laid in piece by piece.

He also uses a dry-brush technique to leave the white of the paper exposed. You can see the white of the paper around the picture frame and in several other spots.

Is any of this important for paintings?

Writing and conversation are linear. We read and write and talk from beginning to end—at least, most of us do.

But a painting is not a linear medium. So-called painterly technique has us moving from place to place with our brush, not getting too enamored of one place on the canvas. We paint where we want to, when we want to, and the finished product doesn't offer too many clues about how it was done.

People see the finished product as a whole. Their eyes flit from place to place. Our main subject is not at the top of the page or at the beginning of our conversation; it's where we want it to be.

Artists can tell the viewer what's important through composition, color, value, pattern, shape, etc. Good artists can control the flow of information.

copyright James Stephens

All rights reserved

More art books and other things from Amazon. Just click this link: